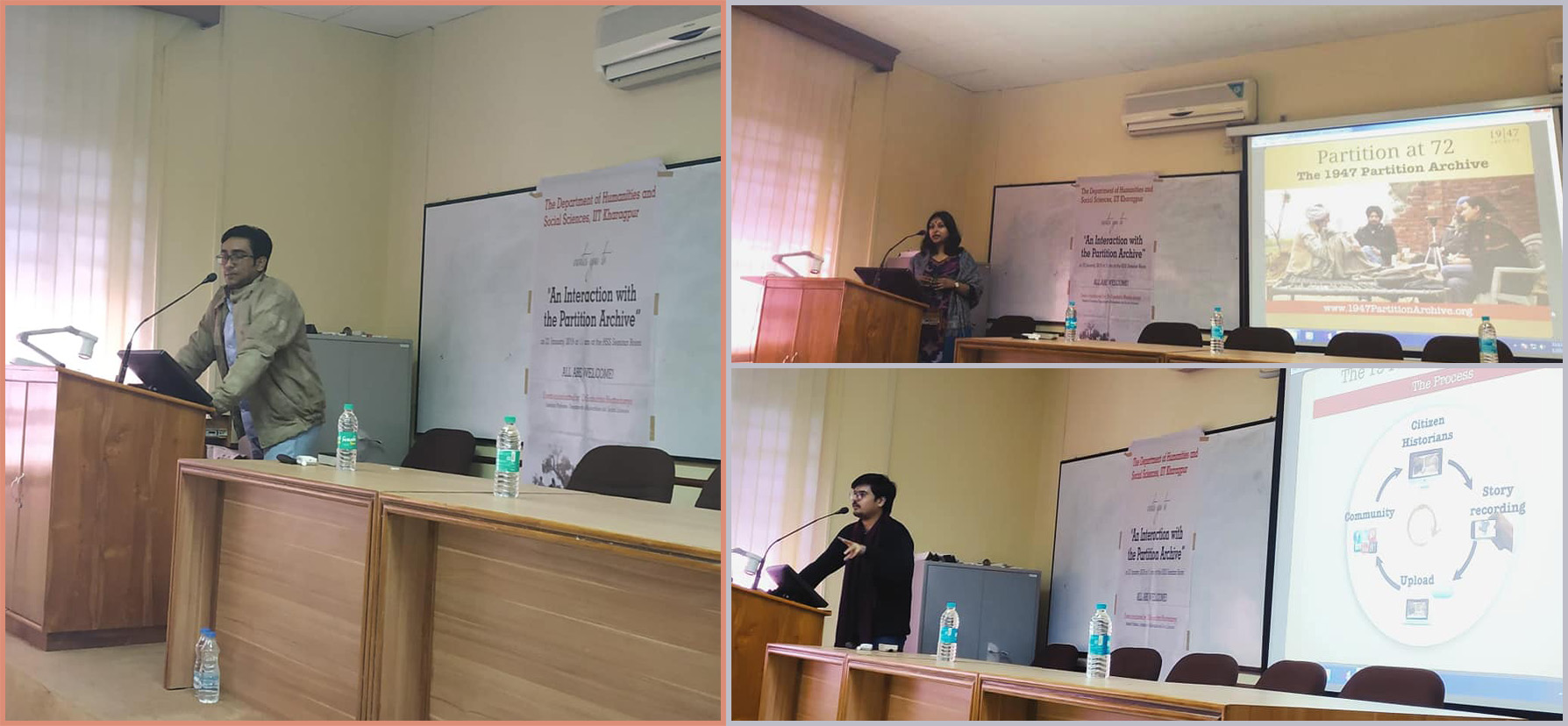

An Interaction with the Partition Archive

Three young boys, almost painfully conscious of addressing what they believed was a way more mature audience than what they probably had in mind. Yet they represented a wisdom that is perhaps as tall as a mountain. The three of them were from “The 1947 Partition Archive”, a globally important organisation. The Partition Archive, a non-profit organization born at Berkeley, with an office in Delhi, has been collecting, preserving and sharing first-hand accounts of the Partition since 2010. The three bright young scholars, who have worked for the organization and continue to work with it, were invited to IIT Kharagpur’s…