In the quest for the hidden past

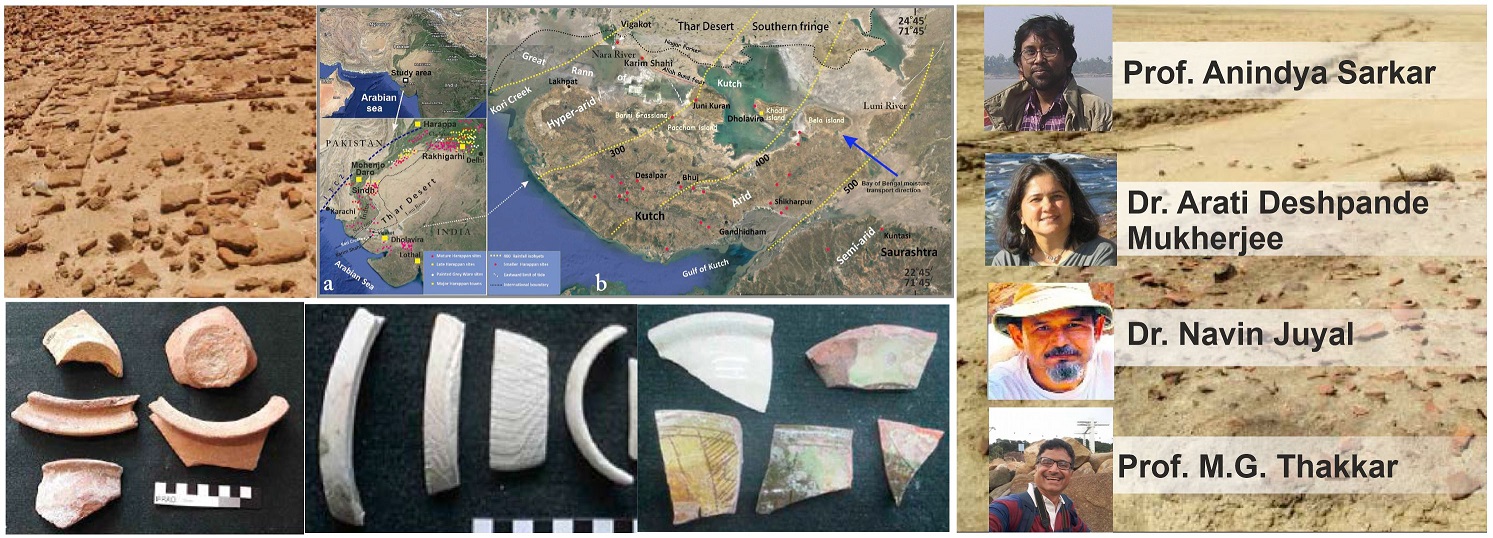

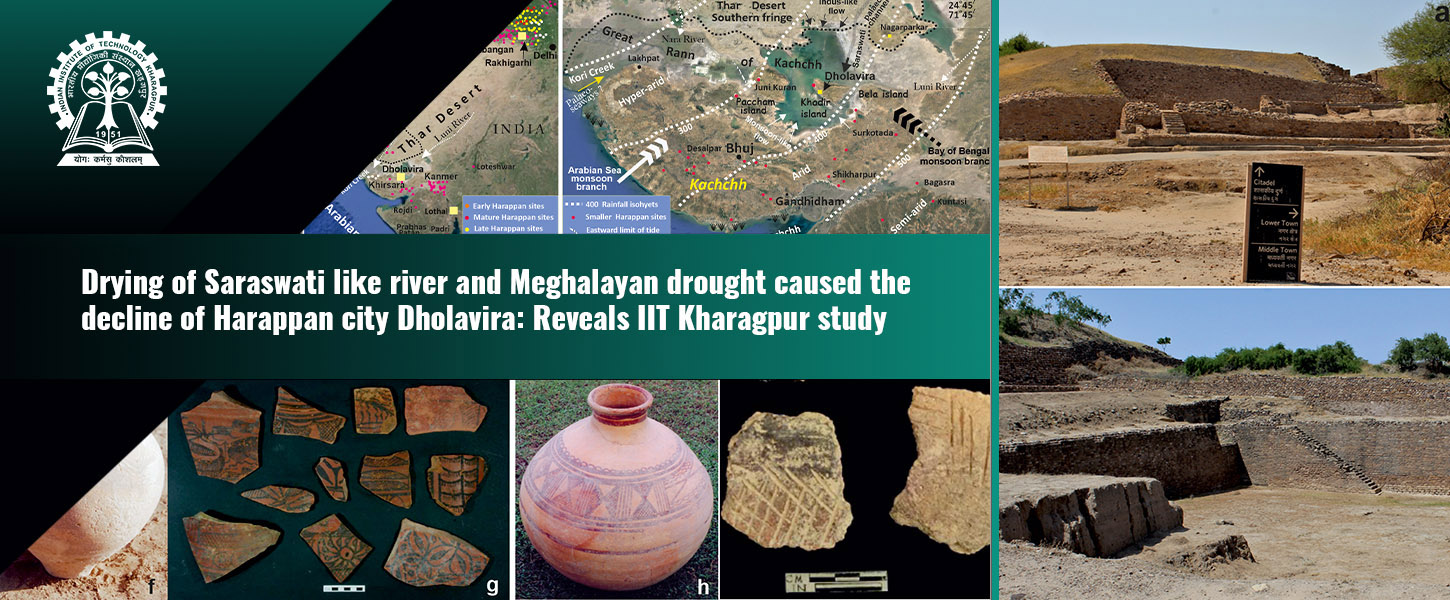

Hindustan Times Economic Times India Today The Hindu BusinessLine Republic Swarajya The Sentinel Assam The Week Dainik Jagran UNI Yahoo News Outlook India TV Times of India Millennium Post Indian researchers have for the first time connected the decline of Harappan city Dholavira to the disappearance of a Himalayan snow-fed river which once flowed…