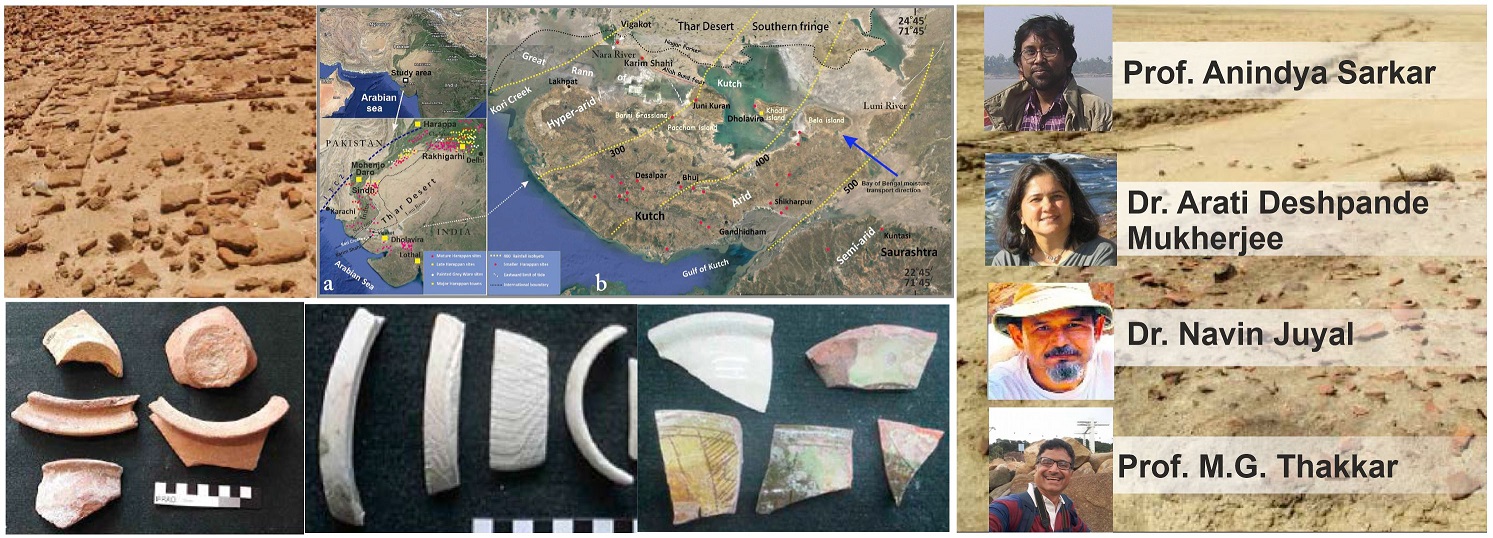

A New Page in India’s History

Times of India Hindu BusinessLine Hindustan Times Nature Asia UNI DownToEarth NewsLive (North East 24x7) India Today Yahoo News The Hindu Millenium Post India Blooms Deccan Herald NewsClick The Week Dainik Jagran Ahmedabad Mirror Swarajya Asian Age A breakthrough discovery by a study led by IIT Kharagpur…